It is quite interesting to note how many trials manufacturers came back from the brink of disaster after the demise of the Villiers motors that powered many of the British built trials machines when the company ceased producing the single cylinder air-cooled two-stroke engines in the mid-sixties.

Competition manufacturers such as Cotton, DOT, Greeves, and Sprite all spring to mind as they all went on to use under-200cc imported engines from Europe. Such brands as Minarelli, Puch, Sachs and Zundapp were used. It is also quite interesting to note how many new trials manufacturers were born after this period as the ‘Micro’ trials machine period was at its height. One of the new brands was Dalesman, which at first used the Steyr-Puch engine from Austria with the company headed by Yorkshireman Peter Edmondson.

Words Copyright: John Hulme

Picture Copyright: Yoomee Archive – Barry Robinson – Malcolm Carling – Eric Kitchen – Alan Vines

Full Photo Gallery at the end of the article

Steyr-Daimler-Puch A.G. of Graz, Austria, was already a mass producer of mopeds and motorcycles. The Puch Maxi moped was a good example, as in 1969 they produced 1.8 million of them, but we must wind the clock back a few more years to 1966 which is really where the Dalesman story begins. The Puch M125 motorcycle was manufactured between 1966 and 1971 and during that period it became a well-proven machine, with its motor becoming its strongest point as the reliability was first class and they would run forever.

By Chance

Peter Edmondson was always looking for new business opportunities, and in 1967 he walked into the Nottingham headquarters of Peter Bolton, who was in charge of importing the Steyr-Puch’s products into the UK. Edmondson spotted the new Puch M125 road machine in the showroom and commented on the potential to make it into a good trials machine. Peter Bolton listened with much interest to Edmondson as he had long been aware of the off-road potential of the robust little 125cc engine and wished to exploit it. He had mentioned this on a visit to the Austrian Puch factory, but the company had felt that the components and parts were not up to competition use. This was despite the fact that a similarly powered machine was then ridden by Belgium’s Joel Robert, who had already tasted international success in the new European 125cc scrambles championship which was beginning to grow on the continent.

Many of the road components could be used or modified for competition use and Edmondson knew this. He took away a new Puch M125 and spent many hours in his workshop using his competition knowledge to turn the machine into a trials model. Once finished he showed the ‘new’ machine to Bolton, who was very impressed with Edmondson’s handiwork. In late 1967 Edmondson travelled to the Puch headquarters in Austria with his new creation.

The factory were very impressed but were not so sure about the machine’s potential against the rapidly growing market and the influx of the Spanish Armada of Bultaco, Montesa and Ossa machinery. They spent many hours looking at Edmondson’s creation, and a similar machine would provide the basis for the equally successful West German team’s mounts for the 1968 ISDT. One of these machines would find its way to the UK and be modified for one-day trials use. Scotland’s Derek Edgar would ride it and soon had many people enquiring about its potential. Edmondson could not wait for the Austrian company to produce its own trials model and enquired about purchasing engines and some cycle components such as front forks and wheel hubs, etc, to manufacture his own machine.

Dalesman is Born

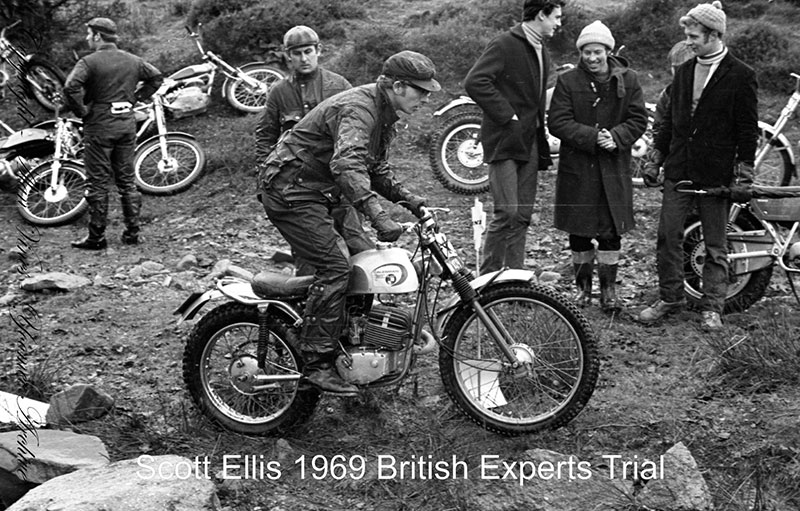

Edmondson had many contacts in the motorcycle trade and called up his friend Jim Lee to see if he could build him a trials frame around the 125cc Puch engine and also incorporate some of the Austrian components to keep the production costs down. In a short period of time the very first Dalesman trials machine was born, and Edmondson was very impressed with frame fabricator Lee’s creation.

Two versions of the 125cc engine were available from Puch, which were the M125 and the M125S. They opted to use the M125S engine and carried out various tuning modifications to improve its performance without affecting its legendary reliability. Edmondson had used his charm at the Austrian factory and negotiated a price of £33.00 for a complete engine, including the carburettor and ignition. Puch had the power to purchase vast quantities of engines and components and could pass on the discounts they achieved to Edmondson to make the whole project financially viable for him.

They produced over 11,000 M125 machines using similar components to the ones Dalesman wanted between 1966 and 1971, hence the price of the parts. Other components such as the front forks came at the bargain price of £6.50 complete and ready to fit. Similarly attractive prices were also negotiated for such items as the wheel hubs from the Puch Moped range. The machines looked the business with the sturdy frame, which although looking over-engineered was both very strong and light. Hyde Components Ltd provided the polished-alloy fuel tank which enhanced the machine’s looks, and it had an overall weight of a mere 156lbs.

The company Dalesman Competition Products was set up and they moved into Ashfield Works Mill, which was leased from the local council in Otley near Leeds in Yorkshire. Jim Lee tooled up to fabricate the frames at his Batley based workshop premises with a young Mick Grant, later of Kawasaki and Honda Road racing fame, also involved. Grant would always race with the large ‘JL’ logo on his helmet to show his appreciation of the support from Jim Lee. Grant would assist with the fabrication of the frames for the new Dalesman as he started his racing career for which he would become famous.

Prison Production

It was a chance conversation with a friend of Edmondson’s which would open the door to having some parts, including silencers, made at Leeds Prison! In any prison you will find skilled inmates, and Leeds Prison was no different. It produced cheap but skilled labour and many Dalesman components were manufactured ‘inside,’ which in turn kept the retail price down without sacrificing the quality. By sourcing many parts and buying in bulk a complete Dalesman trials machine could be produced for around the £110–£115 mark.

With 20 to 25 machines built and sold each week, at a retail price of £170, business was soon booming. The machines were marketed with the help of Peter Bolton who was happy to see the new business flourish under Edmondson’s guidance. Five Puch dealers would unofficially become Dalesman main dealers for the models. The little engines matched the power of the aging Villiers motors that were now out of production, and they soon started to become very popular at Yorkshire trials competitions.

Pete Edmondson went out to Puch in July 1969 at the invitation of the Austrian company to attend one of Joel Roberts’ training schools held at Graz near the factory. He stayed with an eccentric collector of motorcycles by the name of Count Otto Herberstein, who had a financial interest in Puch. On his return from the visit such was Edmondson’s enthusiasm that they moved into the production of Enduro and Motocross machines, which again proved very popular. Soon the export orders, to America and Canada for example, were beginning to fill the order books. Edmondson had a small workforce that included the local bank manager’s son, who looked after the office side of the operation. This was a very good move as he kept telling his father how well the company was doing, and in return Edmondson would always get a very good overdraft facility and bank loan rates when he need to bulk purchase parts for manufacture!

Sold Out

With export orders to America so strong, especially for the growing Desert races where the Enduro and Motocross machines were competing and starting to achieve some success, Edmondson joined forces with a guy called Ron Jekyll who had made his money producing hypodermic needles for the medical profession. He convinced Edmondson that he needed to expand production to meet the growing demand for the machines in the American market and he had the spare money to invest in Dalesman.

Many other ‘cottage’ industry manufacturers were very envious of what Edmondson had achieved and also wanted to start producing their own machines. One of these was Ted Wassell who came down to view the Dalesman operations. Unknown to Edmondson he secretly wanted to buy the company! Wassell had built up a good reputation in the motorcycle industry as a parts supplier, and he now wanted to build his own machines. Bill Brooker had moved to Dalesman from the ailing Greeves Company as Competition Manager and his duties would also involve looking after the export side of the business.

One day a local policeman Pete Edmonson knew contacted him to say that he had seen someone taking his company car. In late 1970 the Americans had decided to invest some money into the Dalesman business in return for a directorship in the company to secure its future. Within a few months they had literally taken over the business as Edmondson concentrated on keeping to production targets. The board of directors, along with Brooker, had voted Edmondson off the board behind his back and out of the business; he had been sold out of his own company, and with the locks changed on the premises he was not even allowed in!

During the period of Edmondson’s Dalesman years he had produced around 1,500 machines and enjoyed much competition success. Pete had the last laugh though as he contacted Wassell and moved to the Midlands in 1971 along with Jim Lee who would make the frames. They went on to produce the Wassell range of machines which became a huge success – before the company folded after a problem over the export orders and not getting paid from the Americans.

The Final Years

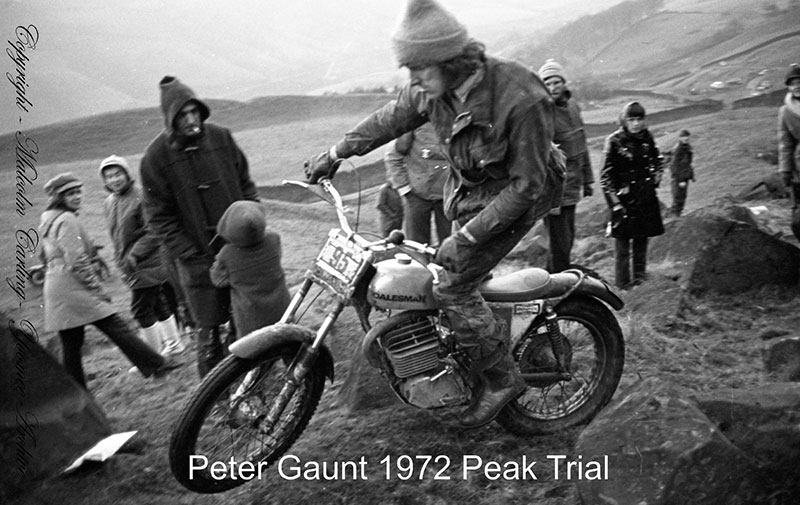

A new prototype trials model appeared in 1971 in the hands of Peter Gaunt, using a new six-speed gearbox Sachs 125cc engine and featuring a front disc brake amongst other things, but the idea never made production. The new machine looked more purpose-like and had a new compact lighter frame, and with extra power from the new motor it started to attract the buying public back. They had fallen out of favour with the brand on Edmondson’s departure when the news got out, he had left the company.

Bigger premises were moved into at the Phoenix Works on Station Road, and they remained in Otley. New Motocross and Enduro models were produced which also moved from Puch motors to the Sachs ones and once again export under the new owners soon began to grow again especially in the lucrative American sector. Despite the machines selling well behind the scenes all was not well, however. The new American investors were milking the company and not reinvesting the profits, and soon it would run into financial problems as suppliers were not getting paid on time, which in turn held production up. They also had to now contend with the Wassell machines in the tough export market and sales begun to suffer.

Production continued through 1973 but with the American sales not as strong as expected, and the exchange rates around the world not as favourable as before, production ceased in 1974. Once again, we had seen a case of profit taking over from passion. Peter Edmondson should be very proud of what he achieved with Dalesman; who knows where it would be now if he had remained in control of his manufacturing empire?